For me, opera begins with Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) – the first of three Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Lorenzo Da Ponte collaborations (the other two were Don Giovanni and Così fan tutte). Of course there were many operatic masterpieces before this 1786 work, even a couple by Mozart himself (Idomeneo and Die Entführung aus dem Serail, for instance), but there’s something special about Le Nozze, a work that has never been out of the standard repertory. Premiering three years before the French Revolution, Le Nozze is a product of the Enlightenment, a time when reason ruled and liberty, fraternity, and equality were ideals worth fighting for.

Opera Sense recommended recordings of Le Nozze di Figaro:

The Marriage of Figaro | librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte

He has promised after that to write a new libretto for me. But who knows whether he will be able to keep his word – or will want to? For, as you are aware, these Italian gentlemen are very civil to your face. Enough, we know them! -Mozart, mentioning Lorenzo Da Ponte for the first time in correspondence with his father, Leopold, in 1783

Lorenzo Da Ponte, The Marriage of Figaro librettist

Lorenzo Da Ponte is one of those exceptionally fabulous historical characters – a masterful poet, adventurer, debtor, and lover. Seven years older than Mozart, Da Ponte outlived the prolific Austrian composer by 47 years. He moved to a young United States of America in 1805, during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson, in an attempt to escape from his overwhelming debts. He eventually assumed a post at Columbia College and was instrumental in bringing Italian opera to the infant nation. Da Ponte librettos are renowned for their wit, and Le Nozze does not fail us whatsoever in that respect.

The Marriage of Figaro | Background

Le Nozze di Figaro is based on the second Figaro play written by Frenchman Pierre Beaumarchais. The first Figaro play, Le Barbier de Séville, introduces the characters of Count Almaviva, Rosina (to become the Countess in Le Nozze), Figaro (the barber), Dr. Bartolo, and Don Basilio, all important characters in the second play, Le Mariage de Figaro, which became the basis for Le Nozze di Figaro. Le Barbier was made into an opera on several occasions, but the most important version today is Rossini’s 1816 Il barbiere di Seviglia (The Barber of Seville), premiering 30 years after Mozart’s Le Nozze. It is important for those attending a performance of Mozart and Da Ponte’s Le Nozze di Figaro to know the characters and background of the story; the composer and librettist knew their audience was familiar with Beaumarchais’ Figaro plays.

Pierre Beaumarchais, French author of the three Figaro plays

In order to understand The Marriage of Figaro, we first need to discuss the events that transpire in Beaumarchais’ first Figaro play – Le Barbier de Séville. In Beaumarchais’ Le Barbier (and Rossini’s Il barbiere), we meet Count Almaviva, a young nobleman (a tenor in Il barbiere, a baritone in Mozart’s Le Nozze) who has fallen in love with Rosina, a rich young lady residing in Dr. Bartolo’s home. Figaro and the Count conspire to steal Rosina from Dr. Bartolo, a plan that ultimately succeeds. The play (and opera) end with the happy marriage of the Count and Rosina. Beaumarchais’ Le Mariage and Mozart’s Le Nozze take place several years after Le Mariage. The entire play and opera are supposed to show a single, 24-hour “day of madness” on Figaro (the same Figaro that conspired with the Count in Il barbiere) and Susanna’s wedding day. Susanna is not a character in Il barbiere; she is the Countess’s (Rosina’s) personal servant in Le Nozze, and she and Figaro have fallen madly in love. Having been married to the Countess for several years, the Count has returned to his amorous ways, fancying his wife’s servant and Figaro’s fiance, Susanna.

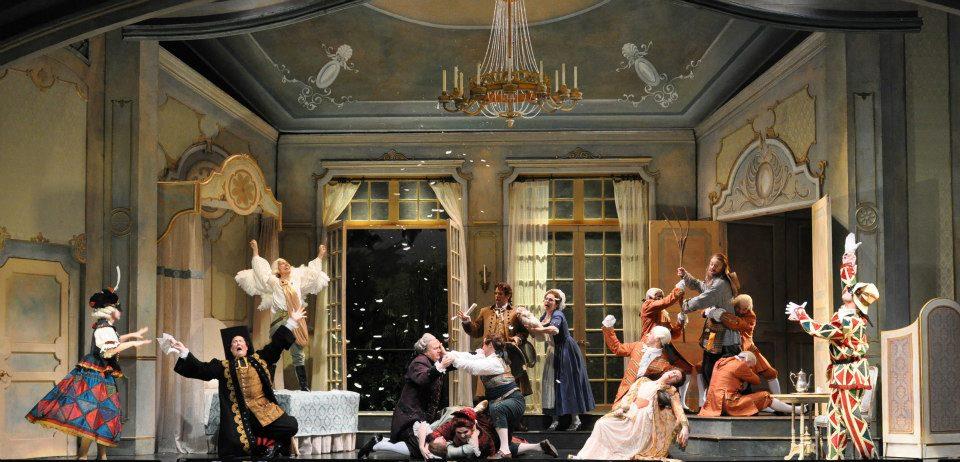

The Marriage of Figaro | Synopsis

Le Nozze is in four acts, and at the risk of oversimplifying things, I would like to present the following rough outline of each act:

Act I – We meet Figaro, Susanna, Cherubino (a page in the Count’s service), Count Almaviva, Don Basilio (Susanna’s music teacher and the Count’s messenger), Dr. Bartolo, and Marcellina (Dr. Bartolo’s housekeeper). We do not, however, meet the Countess (Rosina). Think of this act as the set-up; we meet the characters and learn that the Count fancies Susanna, Figaro’s fiance and the Countess’s personal servant. Figaro learns of the Count’s desire for Susanna and vows to foil the Count’s plans.

Act II – This act opens with a touching aria sung by the Countess, and the entire act takes place in her bed chamber. Figaro, the Countess, and Susanna make a plan to fool the Count, but he, Bartolo, and Marcellina conspire together to prevent Figaro and Susanna’s wedding. This act ends with the miraculous 20+ minute, non-stop finale, one of Mozart’s greatest achievements.

Act III – I always remember this act as the opera buffa act, as there is a silly scene near the beginning during which we realize that Figaro is in fact the illegitimate son of Marcellina and Bartolo. The act ends with the set-up for Act IV – Susanna secretly gives the Count a note that the Countess instructed Susanna to compose. In it Susanna “agrees” to meet the Count secretly, but of course this is a setup at the hands of Susanna and the Countess.

Act IV – Figaro is overtaken by jealousy when he learns that Susanna has given the Count a note, not realizing that she and the Countess are working together to trap the Count. Susanna and the Countess switch clothes and pretend to be one another. The Count, thinking that he is speaking to Susanna when in reality he is speaking to his wife, confesses his love for Susanna, offering his wife the kindest words he has uttered to her in ages, all because he thinks she is someone else (Susanna). Figaro finally realizes the woman he thought was the Countess is in reality his fiance, Susanna. Loudly confessing his love for the Countess (who is in fact Susanna), Figaro infuriates the Count who overhears him. All beg the Count to forgive Figaro and the Countess (Susanna), but he defiantly cries, “No!” Finally the real Countess reveals herself, and the Count is humbled as he comes to understand his mistake, realizing that he confessed love for Susanna to his actual wife, the Countess. The opera ends with the Count asking for forgiveness in one of my favorite scenes in all of opera: “Contessa, perdono! Perdono, perdono!” (Countess, forgive me! Forgive me, forgive me!). The Countess forgives her husband.

Le Nozze is no simple opera buffa; it’s a profound work that explores what it means to be a human being in love. Through Le Nozze we see what it is to be a human being experiencing the waxing and waning of desire, a human being succumbing to the fleeting moments of love and lust’s ecstasy, a human being wrestling with the fire of unimaginable jealousy, and most important of all, a human being embracing the humbling power of forgiveness. Le Nozze hits us everywhere.

I’d like to finish this article with one thing we must always remember: Mozart was 30 years old when he composed Le Nozze. He was 30 years old, five years away from the end of his life. It’s been 230 years since the premier of Le Nozze, and we’re still listening to it, digging into it, judging it, reflecting on it, struggling with it, and relishing in it. Just think of all the great composers it has inspired. Mozart, you eternal, beautiful genius – oh how much we owe you.

1 Comment

Amanda Majeski, Mozart's latest Donna Elvira, Countess, and Vitellia · November 7, 2016 at 5:39 pm

[…] if I can pick just one! I identify with elements of so many characters! The hope of Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro, the faith of Marguerite in Faust, hopefully the grace of the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, but […]

Comments are closed.